Read an article about Jada Griffin published in Inkandescent Women magazine - December, 2021.

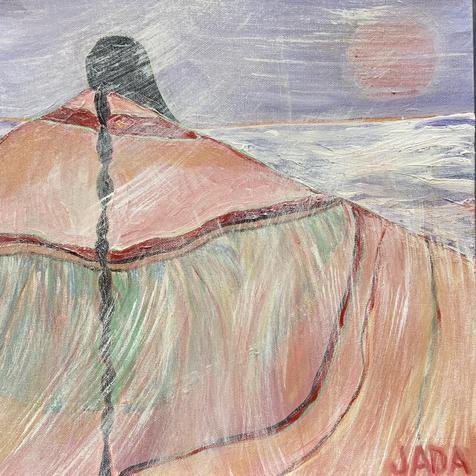

Art by Jada Griffin: Viva La Vida, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 x 2.5 in.

Join Santa Fe Artist, Jada Griffin, for A Meditation on Empty Places, and be sure to check out her amazing artwork celebrating women.

A Note from Hope Katz Gibbs, publisher, Inkandescent Women magazine — “We make pictures because we are painters; we have no choice,” explains Santa Fe artist, Jada Griffin, of Avant-Garde Art. “We sculpt with clay to feel between our fingers the raw material of the earth from which we are originated. Writing is a quest to make sense of the world and to understand our place in it. We dance to experience the ecstasy of being alive. Art helps us to know there is beauty in a commodity-driven existence, to touch the freedom of a geography without borders and a landscape without maps. It is a way of life.”

An American-born and British-educated painter and writer, Jada lives and works in Northern New Mexico on the famous High Road to Taos near Santa Fe. Her works, particularly her paintings of women, are sold internationally and she is a contributing writer to Portland Interview magazine and Navajo Times.

Having studied at Sotheby Parke Bernet in London, Jada has a background, not only in studio painting, but in art history and interior design. In addition to the United States and Great Britain, she has lived in Chile, Algeria, Switzerland, Spain and France and speaks three languages — English, Spanish and French. Jada loves dancing and reading about the history of intellectuals on the Left Bank in Paris during the first half of the twentieth century.

For 10 years she owned her own studio and gallery in Portland, Oregon’s legendary Pearl District, which was named in the early 1980s by her late partner, Thomas Paul Augustine. USA Today rated her gallery the “Best Gallery in an arts district outside of New York City.” The Oregonian newspaper stated, “Jada Griffin is gaining renown as one of the best American abstract expressionist painters.”

“More than anything, my paintings are an affirmation of personal and collective freedom, freedom centered is a generosity, respect and tenderness toward all existence that only true liberty brings,” the artist says.

Jada has always felt inspired by the life-story and art of Frida Kahlo, and her paintings have been compared to those of the famous Mexican in terms of color and emotional vitality. Kahlo suffered throughout her very short time on Earth and yet she always maintained her verve. Griffin has painted numerous intuitive portraits of Frida, including the beautiful Viva La Vida above (acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 x 2.5 in.). Long Live Life was Kahlo’s mantra, a point of view shared by Jada Griffin, and which is mirrored powerfully in her contemporary paintings that advocate for the beauty, strength and freedom of all women everywhere.

It’s a privilege to introduce you to this truly amazing Santa Fe painter. Learn more about Jada’s work at avant-garde-art.com. And please scroll down to read her beautiful essay.

Art by Jada Griffin: Let The Wind Blow Through Your Heart/Winter Blanket, 16 x 16 x 2.5 in.

A Meditation On Empty Places

By Santa Fe Artist Jada Griffin, avant-garde-art.com

“He who loves with passion lives on the edge of the desert.” — East Indian Proverb from Edge of Taos Desert: An Escape to Reality, by Mabel Dodge Luhan

I had been a city creature, but some dimly glimpsed doorway, a portal once shrouded, came instant by instant into focus, and I knew that, like Alice, I would slip down a rabbit hole and find myself on the other side.

The event horizon is an irresistible gravitational pull, a black hole, an opening that connects one universe to another. Floating on a membrane, worlds brush and swell against one another until their collision blisters a pathway from the known to the unknown. An infinite sum total of possibilities indicate mathematical evidence that speaks of a probable other version of myself that I will find on the hidden flank of C.S. Lewis’s magic wardrobe. My apparition is an unassuming fistula, yet it called to me with the transfixing force of drifting yellow butterflies appearing spontaneously in a still and colorless landscape.

The human woman is a wild mustang, a hummingbird, a pronghorn antelope; her physical body is transient, collapsing into a shaft of vapor. Eroticism is real, its limits concealed only by the boundaries of imagination. We have passed through a divide to embody the essence of another place that is beyond and outside of space-time.

A city, I am the heart of any universal capital, my consciousness moves spontaneously upward. Shanghai, with my plethora of new glistening towers, the tallest obelisks to authoritativeness yet seen, I proclaim myself an economic power in the 21st century. On the opposite side of the globe, the sun takes a bite out of the pillars and shafts of my torso, skyscrapers that Georgia O’Keeffe, who was never an urban spirit, painted in the early part of the last century. I am a ubiquitous man-made construct, Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie, all staccato phrase, overlapping cube and jazz-age neon, where the heavens are detected piecemeal, in between the thrust of steel and stone. I pulse with artificial life and the recesses of my concrete canyons are rifts in a metropolis where no animal foot may feel the soil beneath its naked step. It is a vertical geography of mortal creation that no god would presume to build.

Art by Jada Griffin: Intimate Connection, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 x 2.5 in.

A desert is a kind of ocean, but a sea is not a wilderness that is easily penetrated by a land-dwelling beast, at least, that is, in a linear-sequential-thinking context. I am a blue-skinned nomadic chieftain, a Tuareg warrior-prince in a matriarchal line. Black-turbaned and indigo-veiled, my tribal coverings protect my countenance from blowing sands and ward off evil specters. By day I pitch my tent in the curved cup-edge of a dune, a wave of an eccentric kind. By night I sail across and through shifting shoals of silicone-dioxide until I am one with its grainy condition. Over steppe and savanna, camel-mounted in caravan, I am guided by the clear light of Africa’s Seven Sisters constellation. Dates, millet, cheese, butter, cloth, leather, jewels and ostrich eggs are my ancient Saharan trade goods bartered from Egypt in the east, to the southern territories of Libya and Algeria, and deep into Mali, crossing the hot borders on its northern frontier. Gold and silver Agadez crosses, fashioned in flame, sell across the Atlantic and as far away as Santa Fe. My eyes know the arc of a distant horizon, my flesh the temperature of a sheltering sky, my nostrils the smell of bovine urine when it fixes organic dye, my tongue the taste of a salted wind, my ear the sound of a Tisiway poem sung out loud to the beat of a goatskin tambour. Tuareg written language is rarely used, and the history of my people is recorded in oral tradition, passed down in verse as a never-ending story, from generation to generation. My being has no meaning detached from place, and I am in and all around the space from which I come.

I am writer and artist, a poetry-painter of the painted poems of my dreams. A Comanche painted-pony rider of an American Serengeti. I see myself, the blue Tuareg brave in another desert plain. Land-locked, I know the ring of snow-capped summits that lifts in sudden and terrifying magnificence and whose jagged peaks punctuate a Shoshone, Crow, Ute, Cheyenne and Arapaho sky. Your scenic vista was once a watery marshland where mine was a sweeping scape of fire. Earth laments in unrighteous Tuvan throat-chant when it sounds its volcanic legacy from rock and steam below. Black Hills weep tears near Mt. Rushmore, a white culture’s scar in a sacred Red-Indian land. What neck of the woods we dwell in is no small affair. I know that now. It’s as if recurring galactic gamma-bursts, sent by some far-away tribe, have been broadcasting musical messages encoded in light. Their meaning is without a context, for we have yet to evolve a scientific equation of all things, a theory where gravity and quantum physics function harmoniously like notes on a stave. My communication is secret and an intimate exchange. No one else can read the symbols, because they constitute a lust-letter, a glowing and rhythmic symphony that is composed for me alone.

Art by Jada Griffin: Together All Now, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 x 2.5 in.

My pictures come from a forbidden oasis. They are at once mine and not mine, for they surface, almost in spite of myself, from a lake that is both inside of and detached from me, and whose submerged world is accessed each time from a different location – a grassy channel, a fork in the road less traveled, a bumpy old-west wagon trail along the Turquoise Highway. The laguna is uncharted, mysterious, dark and seductive. I wish to be there all the time. It is an energy region of fluctuating boundaries, where visions flow and overlap, unbridled and free, a drug I have never taken and a love I have yet to make. In an oxygen-thirsty body and a literal-minded head, I cannot be an eight-tentacled octopus, a Pacific giant squid, or an orca swimming in the Puget Sound. Oceans are universes that will not be breached and the rivers that course into them are moving corridors that carry someone else’s idea to a completed whole.

It is to high country I am compelled, to Abiquiu at 7,000 feet, the Faraway Nearby of an unexpected woman’s enchanted plateau. I am Mabel Dodge Luhan, Georgia’s Greenwich Village friend. Reaching Taos pueblo in the dead of darkness, I find my authentic self and an adobe house before morning. New Mexico belonged to me before I arrived.

Wilderness. Water is not what comes easily to mind when we think of the place. Wilderness is a wasteland, an untamed and harsh state and a parched and barren sight. We should suffer a bit to be there, be Moses in the Sinai, a bearded aesthete who rarely bathes, inhabits a precipice cave, and wears naught but a rough-woven loin cloth to cover his toasted form. Wet is the fortune of the living and ocean is the fertile soup from whence we came in the beginning. Our very breath is an echo of tides that were witness to our evolution. But the sea can never be more than epidermis, a layer covering something invisible, and a crucible that we cannot come home to. Convulsed in the perfect storm, off the Cape of Good Hope, off the tip of Argentina between Patagonia and Antarctica, we can only glide on its surface, or disappear eternally from mortal reach. I imagine myself, cloche-capped, dressed in a man-suit, a silk wrap (the padparadschah one) about my shoulders and my grandmother’s diamond Art Deco brooch at my neck. I am Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, Jannet Flanner and Solita Solano, Noel Murphy, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, Djuna Barnes and Thelma Wood, Natalie Clifford Barney, Romaine Brooks and Bernice Abbott, (I could go on). I am a suffragette in 1920 celebrating the 19th Amendment, and I cross the indomitable deep from Brooklyn harbor by ship toward Southampton and on to Cherbourg in France. The sea is a circle when I am in its center. I am a Zen-master and the circle is mine because I have dared to draw its difficult and easy circumference. There is no more challenging thing.

Place is a curious concept. Like beauty, its quality is hard to define. If you are impious by upbringing it will be a sentimental fancy, a romantic caprice, impulsive ostentation to expect location to be the catalyst that releases that ephemeral genius unique to us each.

Growing up on a small and crowded island, the elemental root of my being could never find completeness in the Anglo, the Saxon, the Druid, the Viking, in those makers of the hoard of Sutton Hoo and all its Celtic splendor. England is a geography that has grown on me at arm’s length, and it is that distance that has helped me to discover closed-off kingdoms in myself. Soon enough I will revisit Britain’s mystic highlands, its honey-colored hamlets, the bleakness of the moors made eternal in the prose of Thomas Hardy and Jane Austin, for even in the writing of this, there is a hollow in me that misses, with an ache of longing, a marvel long ago taken away.

All of us, if we are honest, know beauty when it is before us. Beauty is convulsive. At the heart of all masterpieces of art is the commitment of its creator, who is willing to confront death to make a work sing. The artist is the Everest-climber who strives to reach the immortal top without knowing if she will make it down alive. The climbing is a meditation that connects the climber to the sweetness of existence. Hindsight of history and the analysis of academic criticism are superfluous to experiencing great creation in the gut. Similarly, we feel it in our core when we are in sync with place, for it participates in mutual benefit and shares a passion that is true. Just as art is a synergy between maker and viewer, landscape is an exchange between the container and the contained.

“As soon as I saw it, that was my country. It fitted to me exactly. It’s something that’s in the air. It’s just different. The sky is different, the stars are different, the wind is different.”

Georgia O’Keeffe

And so too was Georgia O’Keeffe different, for even with a giant and certain skill, she had the courage to be the pioneer who answered the transfixing call of the wide, gleaming stretch of earth that is the Piedra Lumber basin in Northern New Mexico.

This is a compelling land that has lured and quickened the pulse of many a poet. When chief Red Cloud dances, it is in recognition that the beat he hears inside of himself connects him to the presence of every human that has walked across this earth, to the firmament above, to the flowing river and to Raven and Eagle that scream as one, to his ancestors whose histories reverberate across time and lie like jaspers scattered in the spaces where they once dwelled.

Even from where I put pen to paper, I smell the burning piñon upon the breeze, I see the rock walls that gleam transcendental hues, I know the glassy evening arch of heaven that twinkles a billion constellations, I touch the feathered wing above and the Rio Grande below, and I hear the chorus of whispers from centuries of twilight tales told by Navajo, Tewa, Apache, Hispanic, Mexican and European voices. I feel my body electric when I contemplate this unusual and empty place, and I know it is to the wilderness I belong.

Jada Griffin avant-garde-art.com

Paintings, fine-art prints, photography, writing and editing services for creatives.